In this study a term ‘iconology’ means not so much science as a method of reading a work of art by deciphering meaning of symbols presented and compared in that work of art while ‘iconography’ is a knowledge of symbols and meanings connected with them. Thus the object of iconography is symbols and the object of iconology is contents of a work of art. These two fields get through each other because both iconography and iconology must take into account historical, political and (most of all) philosophical context in which the symbol was formed and used in the work of art (antiquity was something completely different to renaissance, classicistic and academic artists). In this study a term ‘iconology’ means not so much science as a method of reading a work of art by deciphering meaning of symbols presented and compared in that work of art while ‘iconography’ is a knowledge of symbols and meanings connected with them. Thus the object of iconography is symbols and the object of iconology is contents of a work of art. These two fields get through each other because both iconography and iconology must take into account historical, political and (most of all) philosophical context in which the symbol was formed and used in the work of art (antiquity was something completely different to renaissance, classicistic and academic artists).

Overhelming power of work of fine arts does not lie in its intellectual content as it is the essence of philosophy. We can admire a work of art even if we cannot read its hidden meaning. The baroque works of art, most of all full of iconographic symbols, filled common people with admiration, delighted and ennobled them, even though they had no idea of those symbols (somewhat like us). In short – one can do without knowledge of iconography. One can also do without reading skill… but not completely. Road signs were invented for foreigners and illiterates but road signs should be learnt as well.

Watching a work of fine art without any elementary knowledge of traditional symbolic is like watching a foreign language film. Spectators can understand some things even without words – it is obvious when someone is crying, laughing when is angry or upset. We can understand the simplest message but it is far more difficult to understand what really is the point of art. The nuances of emotions, wordplays and allusions stay unclear for us. It is the same regarding pictures, sculptures or buildings. Speaking directly, if we buy a ticket to the museum having no knowledge of iconography we lose more than half of its cost as looking at a work of art we are able to see less than half of its content.

To get knowledge of the principles of iconography is like to learn foreign languages but the difference is that iconography is the only universal language (perhaps except for music). If we unite the symbology deriving both from Greek mythology and from the Old and New Testament it will appear that 99% of the European ad American art created till the half of the 20th century use the same language. The 20th century added only a urinal and a tin of tomato soup to this dictionary which is not such a terrible achievement…

In this section we will collect in course of time some basic information relating to the iconography of European art (I will borrow the phrase from the Polish art historian Waldemar Łysiak – the white man’s art) and soon you will find out what pleasure it is not only to watch but also to read a work of art. But there is a kind of nuisance relevant to this matter. The contemporary art seems to be so poor when we put it into perspective.

Illustration above: Cesare Ripa, Iconology, Generosity |

ICONOGRAPHY AND BEGINNINGS OF ICONOLOGY

Aby Warburg (1866-1929)

|

First attempts to explain the content of the work of art systematically by identification and explanation of symbols contained in it were already made by Renaissance theoreticians – like Giorgio Vasari (1511-1574) who in ‘Ragionamenti’ interpreted paintings in the Palazzo Vecchio in Florence, Gian Pietro Bellori (1613-1696) who in his biographies of artists included analysis of their works or Gotthold Ephraim Lessing (1729-1781). Iconography as an academic discipline was practised and developed in the 19th century by such scholars as Adolphe Napoleon Didron (1806-1867) – a French archaeologist, Anton Heinrich Springer (1825-1891) – a German historian born in Prague or Émile Mâle (1862–1954) – a French medievalist. Their interests were focused mainly on Christian iconography and Mâle's ‘l'Art religieux du XIIIe siècle en France’ (1899) still stays in print.

It was Aby Warburg (1866-1929) – a German art historian and cultural theorist who made the first step from iconography towards iconology. In 1892 he completed his dissertation on Sandro Botticelli’s two paintings: ‘The Birth of Venus’ and ‘Primavera’ where he made an attempt to use a methodology of the natural sciences in the humanities fields. In 1898 Warburg moved for some time to Florence where he researched into the art of the transition from the Middle Ages to the early Renaissance and on the influence of relations between artists and their patrons on works of art. Then one of the most important Warburg’s achievements was a critique on a ‘vulgar idealizing of individualism’ which was made by Jacob Burckhardt in his famous work on the Renaissance art. In 1908 Warburg started researches into the astrological symbols which resulted in analysis of the heavens depiction in Old Sacristy in San Lorenzo and detailed explanation of the symbols of the frescoes featuring the months in Palazzo Schifanoia in Ferrara (1469-70).

The iconologic method was developed by Warburg's followers, especially Fritz Saxl (1890-1948) and then by Erwin Panofsky.

In 1942 a German architectural historian Richard Krautheimer (1897-1994) published 'Introduction to an Iconography of Maedieval Architecture' where he used iconographical analysis for architectural forms.

|

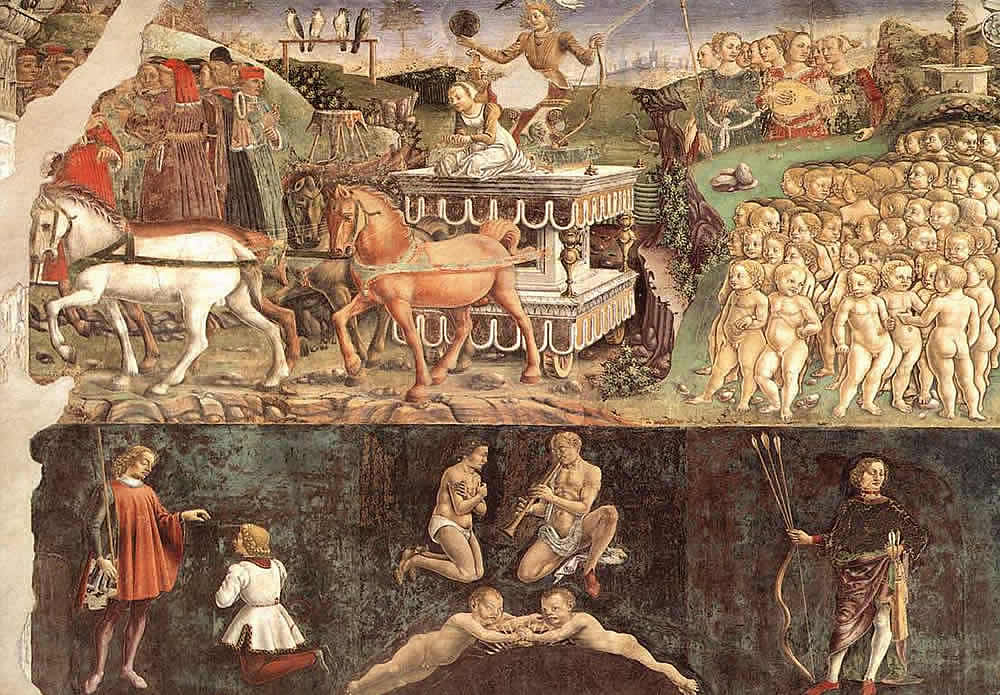

Francesco del Cossa, Alegoria Maja - Triumf Apolla, 1476-1484, Palazzo Schifanoia, Ferrara

ICONOLOGICAL METHOD OF ERWIN PANOFSKY

Erwin Panofsky (1882-1968)

Rafael Santi, Św. Jerzy zabijający smoka, 1504, Luwr

Tintoretto, Św. Jerzy zabijający smoka, 1555-58, National Gallery, Londyn

|

Erwin Panofsky, a German art historian of Jewish ancestry (1882-1968), one of the founders of the 'Hamburg school' (together with Warburg, Saxl and Cassirer), published in 1927 his book 'Perspective as Symbolic Form' and in 1939 'Studies in Iconology' where he used his own three-stage method of the investigaton into the content of the work of art.

Panofsky’s method consists of three strata: (1) pre-iconographical description, (2) iconographical analysis and (3) iconological analysis. Each of them reveals next strata of meaning illustrating at the same time differences between iconography and iconology.

PRE-ICONOGRAPHICAL DESCRIPTION

Panofsky defines forms as configurations of colours, lines and textures depicting objects of the visual world. In pre-iconographical analysis forms must be recognized as motifs (main thematic elements) which are carriers of meaning. Configurations of the forms create objects (human beings, animals, things) while configurations of the objects (i.e. relations between the objects) create events (conversation, kiss). Motifs may be carriers of the intrinsic and symbolic (verbal) meaning. Objects and events have intrinsic meaning. However, there are also motifs of abstract meaning (expressing) like atmosphere, mood, gesture, mimicry. Recognition of motifs and meanings is possible thanks to life experience which is understood as a simple ‘knowledge of objects and events’, completed with knowledge based on sources when life experience does not suggest a meaning of the subject (e.g. old weapon which function consigned to oblivion).

The result of iconographical analysis is recognition of all motifs occurring in the work of art and their basic meaning.

In essence, the aim of this stage is to recognize everything what we can see in the work of art with our eyes i.e. objects (human beings, animals, plants, things, natural elements etc.), events (situations) these objects take part in and – that is very important – to call these objects and situations but only in a basic (primary or natural) range resulting from the elementary life experience. Describing any object or situation we interpret their ‘intrinsic’ (factual) meaning (female, fight) while describing some features of the objects or situations we interpret their ‘expressional’ meaning.

FORMS > MOTIFS : OBJECTS, EVENTS, GESTURES, MIMICS, MOODS

OBJECTS AND EVENTS > INTRINSIC (FACTUAL) MEANINGS

MOODS, GESTURES, MIMICS > EXPRESSIONAL MEANINGS

ICONOGRAPHICAL ANALYSIS

MOTIFS AND COMBINATIONS (COMPOSITIONS) OF MOTIFS are carriers of secondary (conventional) meanings and can be assigned to the subjects.

MOTIFS DIVIDE INTO IMAGES, SYMBOLS, ATTRIBUTES

COMPOSITIONS DIVIDE INTO PERSONIFICATIONS, ALLEGORIES, ANECDOTES

Secondary or conventional meaning is not a result of life experience but of acquired knowledge. E.g. we recognize a knight spearing a dragon as St George, a female figure holding a peach in her hand as a personification of truthfulness and two human figures fighting in a specific way symbolize the struggle between virtue and sin. Iconographical analysis is based on results of pre-iconographical analysis and knowledge of literary sources which acquaints with ‘subjects and images’. On this basis the subject is determined which discovers secondary (conventional) meaning of the work of art.

In short – iconographical analysis connects a motif or composition which has its own basic meaning resulting from the life experience (experience available to all people) with secondary, symbolic meaning resulting from knowledge acquired within definite culture. Thus iconographical analysis has a narrowing character as it discovers meanings which are readable within one culture only. A person who does not know a Christian tradition will never guess what story lies behind St George and will be able to see only a knight killing the dragon. Similarly, a person who is not acquainted with a Japanese culture will not be able to understand a kabuki performance.

How to distinguish between two first stages can be illustrated by this example: a man (object), a dragon (object), fight (event) > St George fighting the dragon (subject). A man is not a symbol of St George here but his representation which primary meaning is ‘a knight’ and a secondary (conventional) meaning is ‘St George’.

ICONOLOGICAL ANALYSIS

Forms, motifs and subjects are treated at the first two stages as properties and features of the work of art itself. In the iconological analysis they became symbolic values built on the national, epochal, religious and philosophical principles. Taking into account the base of the symbolic values gives a work of art a wider context that is the essence of iconology. We can say that iconography can see only a work of art while iconology can see it situated in the cultural space. In this sense a work of art bears witness to its times or to preferences of the artist and/or the principal. It is important that iconological analysis places the work of art in the context of other works of the same and other artists.

Typical questions asked by Panofsky are: ‘Why does a particular artist use the same motif repeatedly in many works? Why do the same subjects appear in numerous works of various artists acting in the same periods of time?

According to Panofsky the basis of iconological analysis is ‘the synthetic intuition’ interpreted as ‘an acquaintance with the essential tendencies of a human spirit’.

Erwin Panofsky’s method used consistently not only allows to understand the basic content of the work of art, decipher the secondary meaning of subjects used in this work and read off their symbolic meaning varying in the context of various epochs but even to indicate such cases where the work of art expresses something completely different from the artist’s (acting under the influence of the epoch and its culture) intensions. The results of sequent stages of iconological method are put through verifying. Pre-iconographical description is confronted with ‘the history of style’, iconographical analysis with ‘the history of types’ (just like under varying historical conditions the same theme was expressed by different objects and events) and iconological analysis is confronted with ‘the general history of symbols’ (like under varying historical conditions the main tendencies of human spirit were expressed by particular subjects).

|

ICONOGRAPHICAL SOURCES

Iconology classics, Warburg and Panofsky, were resolute opponents of ‘highbrows’ ecstasies’ over the work of art leading to unnecessary idealization of the art and distorting its real role in culture. They made efforts (as scientists) to treat a work of art not as an object of esthetical experience but as a document. Deciphering the content of this document requires mastering a scientific method and collecting interdisciplinary knowledge both of origins of the artistic symbols and of varying conditions under which these symbols were deciphered in particular epochs. This knowledge is based on various primary source publications from which over the centuries artists derived manners of imaging contents - sometimes very complicated. |

|

|

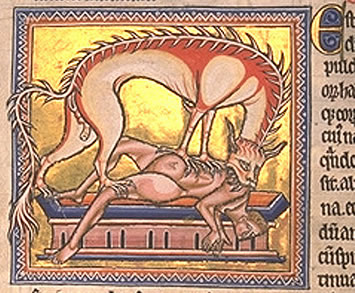

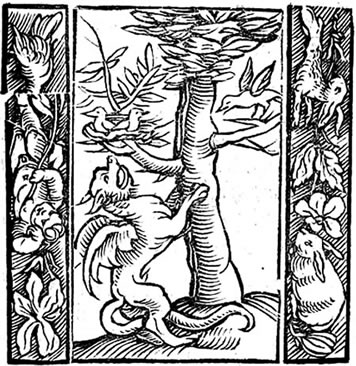

| Gryf, Bizantyjski Physiologus, 1350, Królewska Biblioteka w Hadze |

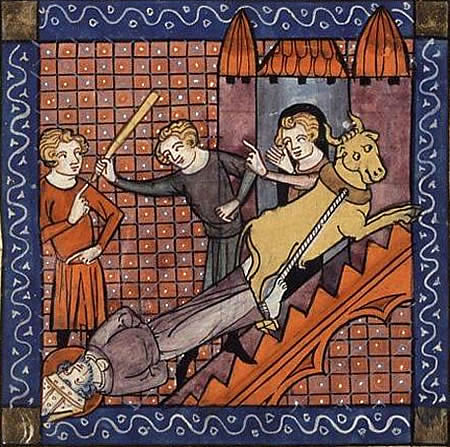

Jacopo de Voragine, Legenda aurea, Męczeństwo św. Saturnina, Paryż, XIV w. |

|

Medieval iconography was based on such works as ‘the Physiologus’ - an early Christian encyclopedia of natural science which first version originated in the 2nd-4th centuries (it consisted of 48 parts depicting stones, plants and animals with allegoric indications of their places in the salvation.) and, most of all, ‘Legenda Aurea’ (‘The Golden Legend’) – a collection of lives of the saints and apocrypha arranged in the order of the liturgical year written in the second half of the 13th century by an Italian Dominican Jacopo de Voragine (1238-1298). The Legend became the most popular collection of medieval religious texts and also a source of narrative plots of the works of art.

|

|

|

| Aberdeen Bestiary, Hiena, XII w. |

Naestiarium z Psałterza Królowej Marii, 1310 |

|

The Physiologus was followed by many bestiaries – medieval rhymed didactic texts which were illustrated descriptions of animals (real and mythical) and their references to Christian faith and ethics. Bestiaries were most popular in England and France although one of the earliest examples is the 12th Book of the Ethymologiae (Beasts and Birds) – an encyclopedia written in the early 7th century by St Isidore of Seville who completed encyclopedic material with proper/corresponding quotations from the Bible. It is worth pointing out that the bestiaries contained a lot of real information about/on animals, e.g. birds migrations confirmed by contemporary science.

Two other examples of famous bestiaries are the illuminated psalters: the Queen Mary (of England) Psalter (dating to about 1310) and the Psalter of Queen Isabella (a wife of Edward II of England) dating to the same time. Both psalters contain comprehensive bestiaries partly patterned after The Historia Scholastica written by Petrus Comestor, a French theological writer of the 12th century.

One of the most famous of over 100 preserved medieval bestiaries is the Aberdeen Bestiary dating to the 12th century.

Many artists created their own bestiaries, e.g. Leonardo da Vinci, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec or Saul Steinberg. |

|

|

| Francesco Colonna, Hypnerotomachia Poliphili, 1499 |

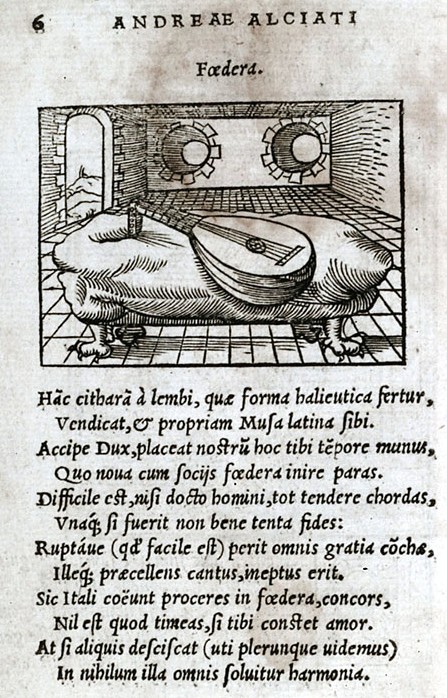

Andrea Alciato, Emblematum liber, Augsburg, 1531 |

|

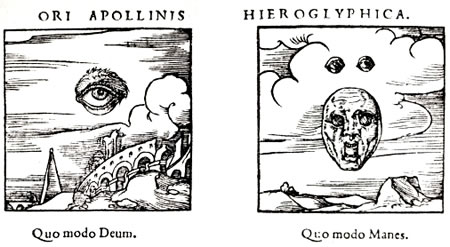

Horapollon, Hieroglyphica, 1505

|

In Renaissance investigations of non-Christian sources of inspiration began along with an interest in classical art. One of the most important was the ‘Hieroglyphica’ written by a Greek philosopher Horapollo who lived at the turn of the 5th century which contained explanations of Egyptian hieroglyphs. The text was discovered in 1419 and published in Venice in 1505.

In 1499 the Hypnerotomania Poliphili (called in English ‘Poliphilos’ Strife in a Dream’) – an allegoric romance by Francesco Colonna (1433-1527) was published. It contained 171 woodcut illustrations showing Poliphilo’s journey through the ideal garden of the island of love symbolizing universum. The work inspired both Albrecht Durer and Gianlorenzo Bernini.

In 1499 the Hypnerotomania Poliphili (called in English ‘Poliphilos’ Strife in a Dream’) – an allegoric romance by Francesco Colonna (1433-1527) was published. It contained 171 woodcut illustrations showing Poliphilo’s journey through the ideal garden on the island of love symbolizing universum. The work inspired Albrecht Durer and Gianlorenzo Bernini.

In 1529 an Italian jurist and humanist Andrea Alciatos (1492-1550) published ‘Anthologia Epigrammatum Graecorum’ - a collection of Greek epigrams translated into Latin and in 1531 ‘Emblematum Liber’ - the immense collection of emblems completed with short descriptions. |

Cesare Ripa, Iconologia, Historia, 1625

|

In 1593 an Italian cook and scientist Cesare Ripa (1555-1622) wrote his book ‘Iconologia’ (Iconologia overo Descrittione Dell’imagini Universali cavate dall’Antichità et da altri luoghi) which became the most popular ‘dictionary’ used by orators, poets and artists to express abstract concepts, virtues and vices, affections and passions. Every concept was illustrated with an allegoric figure or personification completed with a text explaining meaning of the motifs and attributes. The book had been published many times different languages till the end of the 18th century.

Gradually, the elements of symbols of alchemy, astrology and Freemasonry started to get into the content of the works of art, especially in periods when these trends strengthened their positions (it took place every time when anti-religious tendencies increased).

It is difficult to say what was the reason and what was the result anyway accessibility of these works and their huge popularity promoted filling them with more and more complicated content. We could say that they were a kind of ‘codebooks’ by means of which the artists creating works full of formal beauty could hide inside them a deeper philosophical message which could be deciphered only by those who were acquainted with the secret code.

The fashion for bringing hidden literary contents into the works of art was typical for the baroque art although this tendency had always existed in a natural way in the art. The role of the iconographical works and the manner of functioning of many symbols had been changing fundamentally over time and the exhaustion started not earlier than on the decline of modernism and it persists to this day.

At the beginning iconological lexicons served the artists to create works of art and the well educated spectators to decipher their secret meanings. Over time, especially from the beginnings of the 19th century, when the interest in transcendence became increasingly embarrassing and the beginnings of the realism appeared, the iconological code went out of fashion. In the meantime, many symbols (thanks to timeless value of works of great art) appeared in widespread consciousness and became an element of European culture but modernistic exhaustion of this culture resulted in almost complete loss of ability to decipher profound meanings of iconological symbology. Modernistic revolutionists were still well-educated and modernistic art (especially that created by mature artists) was full of references to the inheritance from the past (even if they were contrary – for example Picasso), yet on a mass scale it led to unprecedented flattening of the work of art, first of all totrivialization of its reception. For this reason in the 20th century these books were no longer used by artists to create their works but by rare scientists to decipher their meaning laboriously. |

| In 1968-1976 a German publishing house – The Herder Institute published ‘The Lexicon of Christian Iconography’ in eight volumes. The first four volumes deal with general iconographical concepts (e.g. allegorical depictions of virtues) and non-saints, the next four deal with iconography of saints. This publication, focused on Romanticism and Gothic, obviously is not a handbook for artists (although one could never know) but a lexicon intended for art historians and art researchers. |

| In 1972 a system of iconographical classification compiled in Holland was published in volume form. Its initiator was Henri van de Waal. The system contains about 28 000 motifs and about 14 000 keywords basing on which the art collections are arranged and searched through. Every theme is identified with a special multi-component code. At present the art collections organizing is based on this system both in scientific institutions, museums and in the web. Further information is available on the website: http://www.iconclass.nl. |

| In 1981-1999 the Swiss-German publishers Artemis & Winkler Verlag published ‘Lexicon Iconographicum Mythologiae Classicae’ (LIMC) (The Iconographical Lexicon of Classical Mythology). It is a detailed elaboration completing the mythological source texts and containing the examples of the works inspired by mythological themes since the Mycenaean period and reproductions of these works. |

In 2012 the Polish publishing house ‘Rytm’ published the ‘Dictionary of Symbols’ by Władysław Kopaliński. The author says in the introduction: ‘The present dictionary is not going to be a …

In spite of, or rather for the modesty of the author, the book is worth reading. |

ELEMENTS OF ICONOGRAPHY

Mentioned above the most popular (but not the most important) iconological sources contain material of two types. One of them is a kind of formal patterns - in other words a collection of 'icons' (the term 'icon' should be interpreted here just like in the computer terminology) used in the artistic code and the ways of presenting them. These patterns are recognizable at the pre-iconographical level of analysis in Panofsky's method. Thanks to these sources we are able to determine precisely what a painting presents and recognize its elements properly. As a matter of fact, the most important source of this kind of material is life itself but in the formal layer a work of art can depict objects and human figures which do not exist in reality (therefore a material model of this product of imagination must be created) or such of them which character we are not able to recognize because of cultural, civilization or historical differences. It should be simply determined whether an elongated object held in the hand by a portrayed person is a scepter, crook or lance, what are (were) these objects used for and what are their distinctive features. This type of sources is an ‘archive of icons’ including practically every kind of encyclopedic collection of informations on objects filling both material and immaterial reality. It is noteworthy that Physiologus (mentioned above) in fact was not a handbook for artists but an early medieval equivalent of Enyclopedia Britannica.

The second kind of materials makes up what Panofsky called the ‘familiarity with themes and imaginations’. In old times it could be a result of an intensive religious and cultural life (even illiterates could participate in it). Nowadays it is simply a humanistic education. Thanks to this ‘familiarity’ trivial objects and typical figures can be put in context and endowed with the power of creating associations. These associations are the content filling the work of art as the object of art always tells more than it depicts. These associations are the content filling the work of art as the object of art always tells more than it depicts.

Since the work of art tells ‘the essentials’, the essential areas are essential for iconography as well. The question – which areas are essential – is easy within history of art. The essential areas are those from which the symbology of the most valuable works of art derives. In turn, the question asking which works of art are the most valuable is also very easy if we agree to accept the main demand of the classics of iconography. They considered that a task of iconography is not to estimate but understand. From this point of view, it is an important guidance for iconological analysis that: firstly, the art of a particular epoch wasdominated by particular themes and symbols, secondly, particular works were considered as extremely valuable in view of that epoch and, similarly, that the previous hierarchies were respected or negated in other epochs.

In a word, the most important iconological knowledge is the acquaintance of spiritual fundamentals of subsequent epochs, their ideals and moral norms – yet watched not from a contemporary perspective (because it tells about us and not about a work of art) but from their own unique perspective.

For a tracker of meanings of artworks (antique, medieval, modern or contemporary) his own attitude towards religion, witchcraft, magic, alchemy, occultism, mythology etc. is of no importance. If he wants to understand a work of art – he must have knowledge of these areas. He must be ‘familiar’ with them. |

EVENTS, FIGURES, OBJECTS, CONCEPTS

Iconographical schemes used in art arise as result of interaction of four groups of elements: events, figures, objects and concepts.

Events are mythological or historical facts which were decisive in the history of the world, mankind, communities or individuals. They usually concerned such precedential events creating ‘types’ as the creation of the world, birth, fratricide committed by Cain, death etc.

The actors of the events are figures which are carriers of symbolic values thanks to the 'typical character' of their fates. Every figure has its 'passive' dimension thus their fates indicate the influence of some 'driving forces' and its 'active' dimension' thus thanks to their personal features and emotions they bear witness to abilities (or weaknesses) of human spirit.

Neither these features nor emotions (nor any general abstract concepts) can be illustrated directly. They are manifested in action – to which also objects belong (in the sense that an acting figure can also be an object). If a 'typical' figure takes part in the 'typical' event which is an evidence of any 'typical' feature or concept then all objects taking part in this event become a kind of 'types' themselves and get symbolic meaning – they become symbols and give their physical form to the concept which pictorial presentation/depiction is impossible.

Process of transformation of a subject into the symbol was autonomous and slow but creating a compact iconographical system was most often (though not always) a 'programmed' process i.e. created by some conscious action. Also various kinds of templates and lexicons made favourable conditions for its development. In the 15th century there was even a compositive form compiled in order to arrange and explain meanings of the symbol. The form was called an 'emblem'. In 1531 the first printed collection of emblems appeared in Augsburg under the title 'Emblematum Liber'.

The emblem consists of three parts: a sentence (motto, lemma) describing in maximum five words the essence of the symbolized content, an image (icon, pictura) depicting a symbolic form (object, figure, event) and an epigram (subscription) explaining (most often in the poetic form) the meaning of the symbol and its wider context.

The object that was given a symbolic meaning can be used in the work of art to present abstract concepts or for identifying figures. When it is used as an element assigned (added) to the figure or allegory it becomes its attribute (in Latin: attribuo – ascribe, assign). For instance, the attributes of the Allegory of Justice are scales and a blindfold, the attribute of Death is a scythe ('harvest of death'). The attributes can be generalized to various degrees - e.g. a scepter as a symbol of royal authority identifies every (whichever) king, the lily as a symbol of virginity symbolizes the Virgin Mary and the keys are an attribute of St Peter referring to Christ's promise given to him: 'I will give to thee the keys of the kingdom of heaven'.

There is no precisely determined/defined difference between a symbol, emblem and attribute. An attribute is a mere manner of functioning the symbol. The following relationship can be applied to the rest of concepts:

- an object (by its participation in the event) becomes a symbol

- a symbol depicted graphically becomes an icon

- an icon together with a sentence and explanation of symbolized content becomes an emblem

- an icon or an emblem added to the figure or personification becomes an attribute or, as an independent element, performs a function of a symbol.

Naturally, this scheme is simplified very much, as not only an object (objects) becomes a symbol but also events in which these objects take part. The functioning of the symbol undoubtedly depends on to what degree the symbolized content is generalized and how the symbolized events and figures are fixed in the collective consciousness. An iron gridiron itself means nothing special and it brings other (than common) associations only to those who are familiar with St Lawrence martyrdom. Therefore the gridiron becomes a readable attribute of a proper figure. The crown of thorns identifies Christ clearly because it is not a symbol of physical pain but rather an attempt to humiliate God however the cross is a symbol of sacrifice only for virtue of His person as in ancient times crucifixion was a method of death penalty execution usually used for common criminals.

Iconographical schemes were used in art in many ways and – on the whole – the simpler the purpose of the work was, the simpler means were used. If a guiding principle of a work of art was only a didactic or illustrative (or even decorative) purpose, it was enough to use the plainest attribute or even emblem (an icon with a description) and ram into the audience’s heads association of scales with a concept of justice. Even extremely incompetently made stone figure of a woman holding scales in her hand will be interpreted properly. In works which contain many themes the attributes usually serve as identifiers of figures, completing the main theme with subplots (secondary themes) which show didactic or moving fates of these figures. By that means they deepen the sense of the artwork showing the spiritual tradition of its donor and even his political affiliations.

One of examples of using a few attributes in a work of art (anyway filled with a lot of content) in order to introduce additional plots is 'The Last Judgement' by Hans Memling. The angels floating over Christ are carrying the Instruments of Passion (from left to right: a column and a whip, a cross, a crown of thorns, a hammer, nails, a lance and a sponge set on a reed) – representing all stations of the Passion and the Cross. The symbols are completed with a lily (the Immaculate Conception) and a flaming sword (Armageddon – a final battle between the forces of good and evil). Naturally, these attributes still are ordinary objects but the history of Crucifixion is so deeply encoded in the collective consciousness that even people who are completely religiously indifferent are able to decode their symbolic meaning without any problems. Growing up in still lively culture they are, willingly or not, 'familiar with the themes and images/ideas'. However, there is probably quite large group of spectators who – watching Memling's work – rack their brains why those angels had dragged a whip and a hammer on such a solemn occasion...?

We have been familiar with the themes and images of Christian iconography for at least two and a half thousand years and that is why we can interpret many symbols almost automatically. They became fixed so firmly thanks to the poetical power of canonical texts (in addition to sanctity of the theme) - most of them are outstanding literary works. However, the whole iconography contains a huge amount of symbols alluding in the pictorial layer to the main content which is unclear and unreadable beyond the epoch and its culture.

The emblem shown beside (published by Andrea Alciati in 'Emblematum Liber' in 1534) consists of lemma Foedera (The Treaty), an icon depicting a lute lying on the table and an epigram. It contains a dedication for Duke Sforza which was to persuade him to make peace and sign the treat. It needed to agree on terms/conditions just like many strings of the lute need fine tuning to gain/achieve/get harmony. A lute and a lyre were popular metaphors of unity, entirely readible for Renaissance addressees.

The associations between a many-stringed instrument and the necessity of tuning and between tuning and getting harmony are possible to appear in contemporary minds, but dedicating any musical instruments to contemporary politicians keen on playing – but leading roles not instruments - could be misinterpreted.

Taking it seriously – most symbols presented in works of art are banal objects. Only after having been linked with thousands of threads to the epoch, its values, customs, 'themes and images' they became symbols full of meaning. On next pages we will look through the themes and images of various iconographies starting with Christian iconography.

Emblemat "Foedera", Emblematur liber, Paryż, 1534

|

|